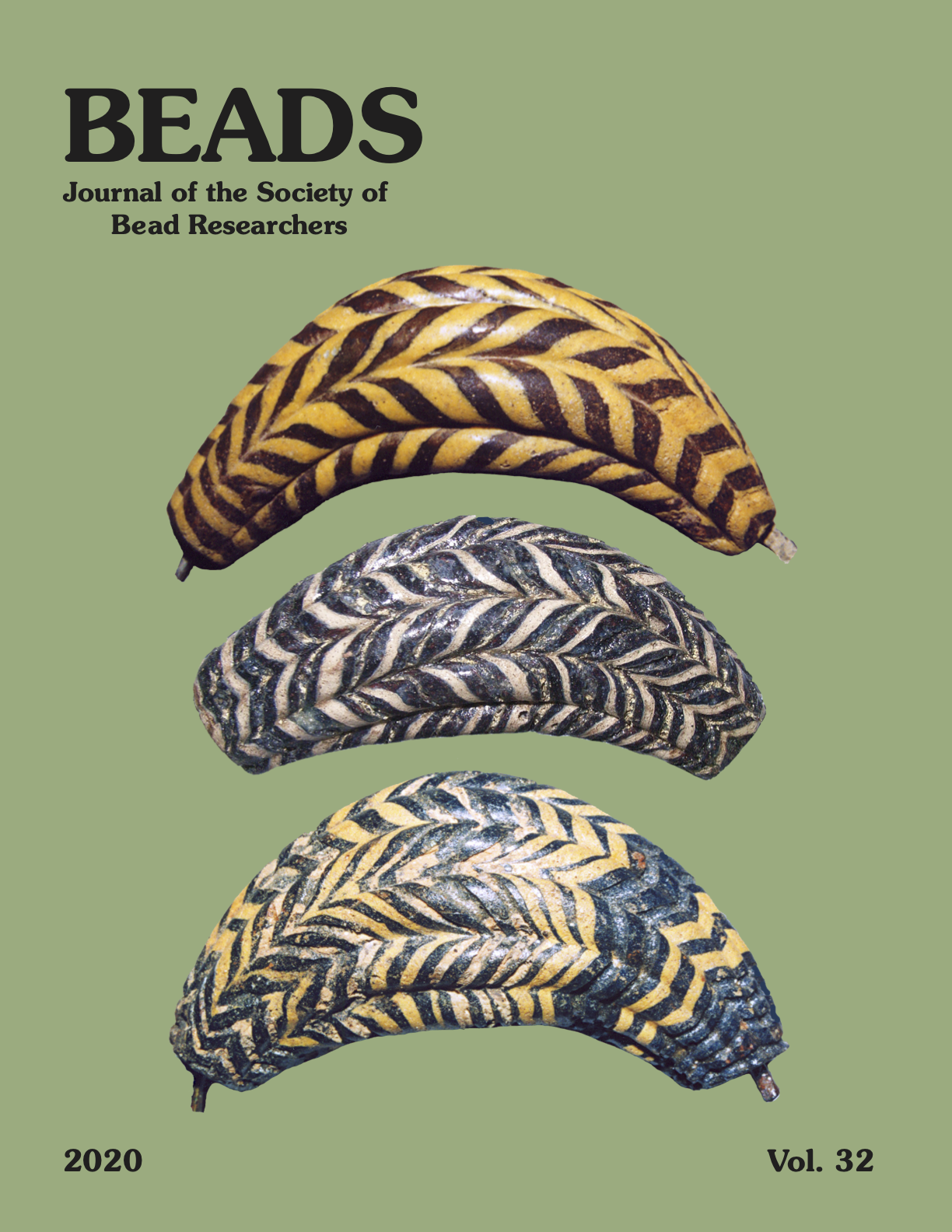

The Large Glass Beads of Leech Fibulae from Iron Age Necropoli in Northern Italy

During the Iron Age, around 700 BC, artisans in northern Italy produced bronze bow fibulae decorated with large, elongated, leech-shaped glass beads. These extraordinary brooches, known only from women’s tombs, required special technical knowledge and skill to create. This article provides an overview of these adornments as well as insights into their production technology, chemical composition, and origin. The wide variety of these objects suggests the existence of several local glass workshops.