Heirloom Beads of the Kachin and Naga

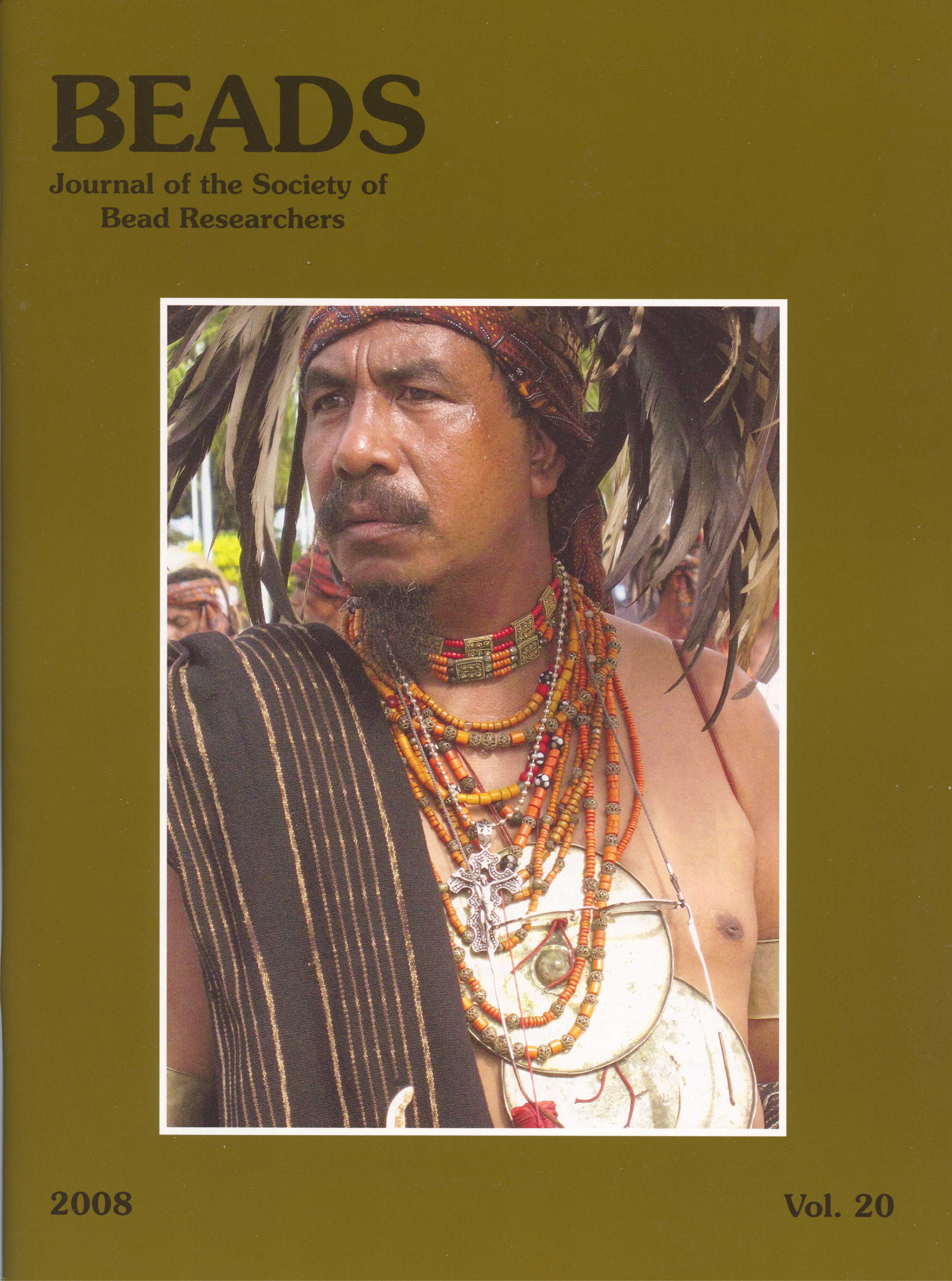

The heirloom beads of the Kachin and Naga - known respectively as khaji and deo moni - were discussed at length in British-colonial literature, but remained unidentified until the present day. The homelands of the Kachin and Naga straddle the northern Burma/Northeast India frontier. Safe from the great civilizations which rose and fell in the plains, the cultures of these hill peoples remained relatively intact until the arrival of the colonial British in the 1830s. The author's research reveals that khaji and deo moni are orange Indo-Pacific beads of a type traded from southeast India - probably Karaikadu - between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200. They were found by the Kachin and Naga in ancient graves. The trade that brought these beads to the region operated at a considerable scale. Ivory and fragrant oils destined for the Mediterranean world were exchanged for Indo-Pacific beads, cowries, chank shells, and carnelian beads, ornaments still worn by the Kachin and Naga today.