Ceramics and Glass Beads as Symbolic Mixed Media in Colonial Native North America

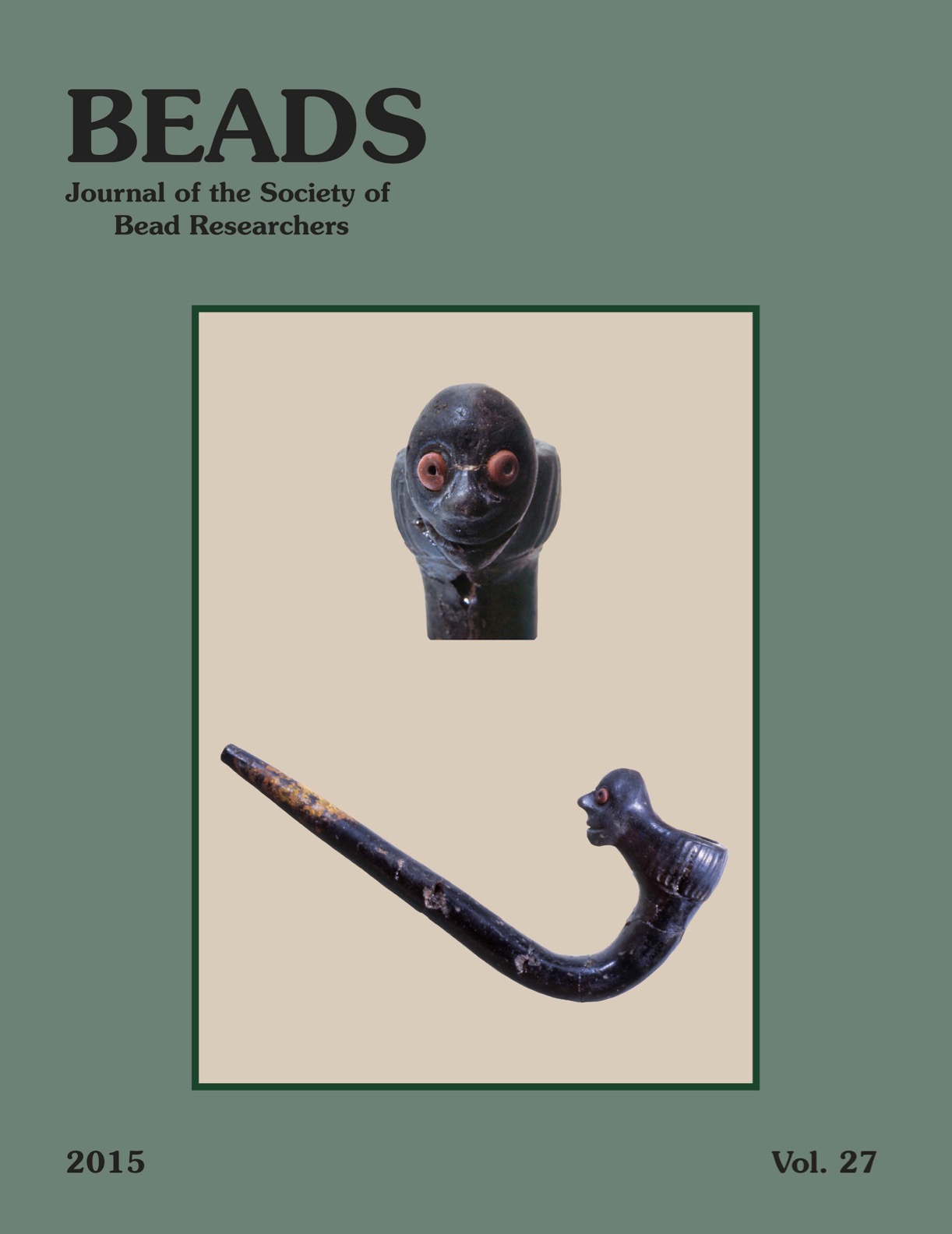

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Native Americans rarely adorned ceramic objects with glass beads, despite the millions of beads introduced by Europeans through trade. Bead-decorated ceramics have been reported from only nine sites in North America, perhaps due to a tendency for archaeologists to overlook or misclassify bead-inlaid pottery. The 40 artifacts represent widely divergent ethnic groups separated from each other culturally, as well as by great distances in space and time. Yet they display a remarkable consistency in the pattern of bead arrangement and use of color. Colored glass beads stand in for human eyes in effigy smoking pipes and white beads encircle the mouths of pottery vessels. Rather than examples of idiosyncratic coincidence, crafters of these objects communicated broadly shared ideological metaphors. These rare artifacts speak to the interconnectedness of ancient Native Americans and to related worldviews developed over centuries of intercommunication involving mutually intelligible symbolic metaphors.