World War I Turkish Prisoner-of-War Beadwork

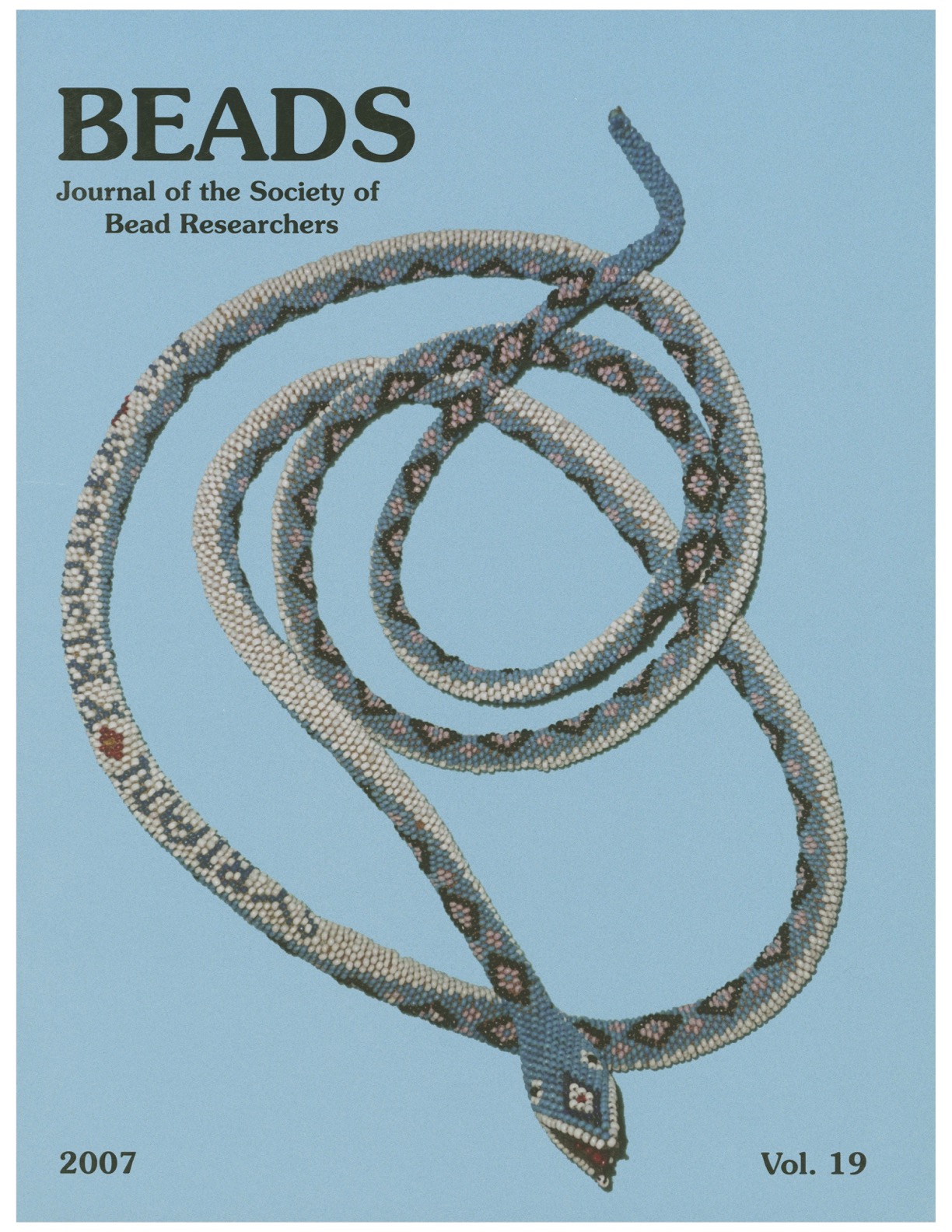

Drawing on the rich tradition of textile crafts in the Ottoman Empire, Turkish soldiers incarcerated in British prison camps in the Middle East during and immediately after World War I made a variety of beadwork items to relieve the boredom of their prolonged imprisonment and to barter or sell for food and other amenities. Best known are the bead crochet snakes and lizards, but the prisoners also used loomed and netting techniques to produce necklaces, belts, purses, and other small items.